Simple Tech: ESP and Traction Control explained

We've been controlling cars for over a hundred years and our research shows we've been doing with rare exceptions, a terrible job of it. Traffic has killed more people than all the wars in history and mechanical failure is usually a much smaller factor overall than human error.

Which is why our cars (and increasingly motorcycles) have more and more computing power - to keep us safe. Last time, we spoke about ABS and EBD. This time, let's talk about the next steps - traction control and stability programs.

Traction Control or TC works to prevent the loss of traction under cornering or in difficult conditions. It usually works with the ABS system or an active differential or both. With just ABS, TC can brake a wheel that is detected - by wheel speed sensors - to have less grip than other wheels which causes the extra torque to be directed to another wheel with more grip. Which improves the driver's control over the car.

An active differential is able to channel more power to the outer wheels during cornering. This cuts yaw (the turning movement of the vehicle around a vertical axis) and offsets the effects of centrifugal force (which wants to push the car out of the turn). This system comes from Formula One where it was banned but is seen in high performance sportscars.

The third way for TC to work is to control engine power output. Specifically to cut torque output by, for instance, shutting down one or more cylinders momentarily.

But while traction control systems primarily target spinning wheels to restore traction and control, stability programs are more powerful systems that include traction control but work towards ensuring that the vehicle does what the driver thinks it should in response to his or her inputs.

Like the traction control and ABS systems, it uses wheel speed sensors to get a picture of the traction available and how it is being utilised. But it also has access to yaw (how the car is turning), throttle position (how much acceleration does the driver want), steering angle (how fast does the driver intend for the car to change direction), lateral acceleration and more.

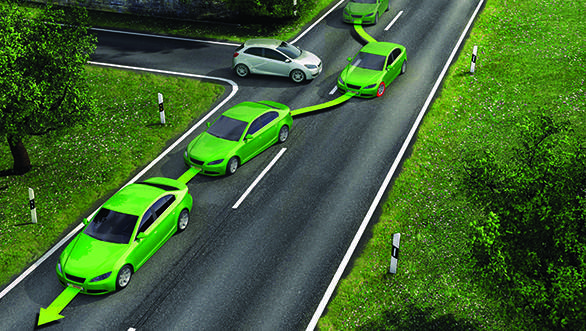

It uses this data to create a picture of where the car is heading in the real world, and where the inputs the driver is giving should be taking it. When the two do not coincide, the stability program intervenes. Take for instance an understeering car. The stability program will see that the steering angle is much sharper than the actual trajectory of the car and intervene. This could be by braking one or more wheels, cutting or redirecting power and a variety of other interventions.

An electronic stability program is always on and in higher performance cars, the driver can select modes where the computer allows some latitude to the driver before it cuts in and saves his or her skin. Skilled drivers may also be able to turn ESP off entirely. This is because certain manoeuvres that require driver skill, like a sustained drift or a powerslide are marginal situations which the ESP will generally interpret as undesirable and it will intervene to restore control.

But the presence of ESP is so important that all cars show clear indications of both when the ESP is off, or when the ESP is intervening. But while performance enthusiasts tend to be biased against ESP and its abililty to cut out the fun, the truth is that the safety quotient of having ESP cannot be understated. Authorities in the USA, Australia, Europe and Canada now require ESP to be a part of the standard equipment and most other nations will probably follow suit shortly.