Simple Tech: Types of differentials explained

If you read Simple Tech last month you know that simple (aka open) differentials allow the two wheels on one axle to rotate at different speeds which is critical for changing direction.

However, an open differential ignores the actual difference in the rotation of the two wheels and sends equal torque to both. Sort of like a mum who keeps trying to feed both her kids without taking note of their appetites. Torque is only useful if the wheel has enough grip to be able to use it. The more grip, or traction, to be exact, the wheel has, the more torque it can use. For practical purposes, we assume that on clean tarmac, all four wheels have equal traction. In this situation, an open diff works well enough. But what happens if, for instance, half the lane is wet? Or you have to put two wheels in the dirt to pass a stuck car? In this case, one wheel will have significantly lower traction than the other one on that axle. If you give this wheel too much torque, it'll just spin uselessly instead of driving the car forward. Which means despite having two wheels on the driven axle, the car will have one wheel and half its torque to drive with. Trouble.

Enter the locking differential. This type of differential adds the ability to lock (in effect, bypass) the differential. The wheels can no longer rotate independently of each other. Which means the wheel with traction will, in effect, get all the torque that the other wheel cannot use to push the car forward. The increase in torque helps the car out of this difficult traction situation. A locking differential, naturally, has a specific use and is usually manually activated when needed and then turned off. Locking diffs are considered hardcore off-roading equipment.

Between the hardcore off-roaders and the simple open-diff equipped cars lie vehicles that actually do see wheelspin but don't need locking diffs either. For example, a sportscar cornering at high speed could experience wheelspin and/or a loss of traction. For this situation, high performance vehicles use a limited slip differential also known as an LSD. As the name suggests, the LSD doesn't fully lock the differential. It effectively responds to the traction situation by increasing or decreasing torque according to whether the wheel can use it or not. Which is why LSDs are considered performance equipment and are usually operated mechanically (with clutches) or electronically (by using the brakes or electronically controlled clutches).

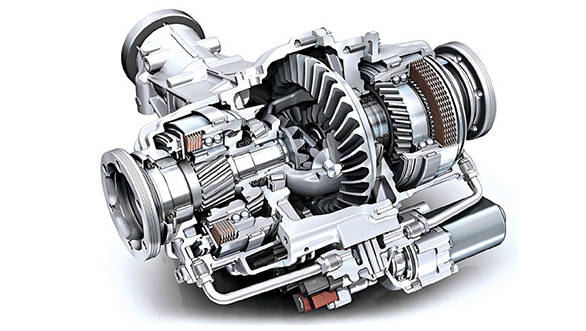

As we've seen, electronic controls are usually more accurate than mechanical equivalents and that's where electronic differentials come in. The basic form controls a clutch or similar mechanism to lock and unlock a locking or limited slip diff. This is a complex piece of equipment because it adds a clutch to the open diff. A simpler form is the electronic diff that uses the brakes to force the diff (usually an LSD) to send torque to the other wheel when the system detects wheelspin. This kind of system is usually employed with the traction control system and is a very simple system in nature and hence, quite popular.

The final and most cutting edge form of the diff is the active differential. This is a system that brings to the diff its own ECU that reads data from a raft of sensors to understand what the vehicle is doing (yaw, steering angle etc) and uses clutches or brakes to accurately distribute torque across the driven wheel to finely tune the power to the driver's intentions and the available traction and curb under- or oversteer. Active diffs got so good that they were banned from the WRC after 2006 and can be found in high performance cars from a number of brands including Ferrari, Mitsubishi, Audi, Subaru and Volkswagen.

For more on Simple Tech, click here.