Five-time Le Mans winner Derek Bell on spending a lifetime in motorsport

"In these conditions you should always be in a longer gear," Derek Bell says to me looking out at a rain-soaked Monte Carlo. A host of racecars that are competing in the Historic Monaco GP's Group E class are heading down the track, and Bell's sprung up midway through our interview to have a look at them go by. I really can't blame him for it. The only thing that was preventing me from jumping up myself, was the fact that I was having a conversation with Derek Bell. The Derek Bell. And one simply does not spring up mid-sentence while talking to a five time Le Mans winner. That's almost like driving a single seater at the Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps, and stopping in the middle of Eau Rouge just to take in the scenery. Forget being rude, it's motorsport blasphemy!

"He should be up a gear," Bell continues, looking at the cars going by. "See, these guys are further back, and they're less experienced. The sooner you can get the next gear, you should. Then it's not so violent," he says, watching as some of the drivers are struggling to handle those historic grand prix machines in the rain. Since it's advice from someone with a fair amount of experience, you know, five-odd decades in motorsport, I make a mental note of what he's saying in case I ever find myself strapped into a single-seater barreling down the streets of Monte Carlo in the rain. Stranger things have happened, after all. One half of my brain is saying, "Soak up every word of wisdom that you can from this man, for he is, undoubtedly, the motorsport equivalent of Merlin." The other half of my brain is saying, "You? Driving around Monaco in a single-seater? When pigs fly!" Even as the voices in my head continue their raging argument, the cars all go around the corner, out of sight, their engine notes receding into the distance. And then Derek Bell and I are able to carry on our conversation, which, when you think about it, is a pretty ridiculous sort of statement to be able to make.

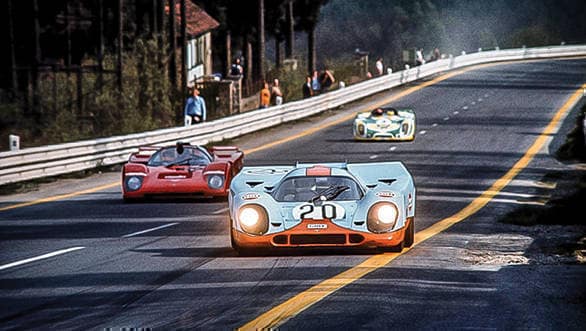

Bell in the John Wyer-designed Porsche 917LH that he drove at Le Mans in 1971

Bell in the John Wyer-designed Porsche 917LH that he drove at Le Mans in 1971

"You know, when you talk to the older brethren of racing they all say, 'What an incredible career you've had,' but it wasn't totally what I wanted. I wanted to drive Formula 1," Bell says slightly wistfully. It's something that one doesn't really expect to hear from an individual as accomplished in motor racing as he is. After all, in addition to those five Le Mans victories, Bell has also won three Daytona 24s and two World Sportscar Championship titles. And he's driven competitively in various other forms of motor racing. But, believe it or not, Derek Bell, like us, is human. And to be human, means to yearn for some things and to regret others. And sometimes the things one yearns for and the things one regrets are the same. "The only personal regret, obviously, is that I would love to have done a really good year of Formula 1. But then, that is washed out by the fact that I had such a great time in prototypes and sports cars," he says. Bell doesn't pause a whole lot while talking, because he's got quite a lot to say, working out the answers to a few questions mid-sentence. But this one time, he does pause just for a moment. "How could you have everything?" he asks, shrugging.

Let's face it though, another foible that is inherent to the human race is that we really do want everything. And when you add the competitive element of motorsport to this equation, things tend to get a little complicated. Bell himself says "Everybody has to be selfish to be good. Not that I wanted to be selfish." Like so many other racers, he was in pursuit not only of the giddy sort of joy that comes from driving racecars, but also of the sense of euphoria that comes from winning. That top step of the podium, and the trophies and champagne that go with it, are manna sent by the racing gods. And for Bell, the fact that he was able to do quite well in other series, but not in Formula 1, certainly did bother him. Staying motivated despite the fact that he wasn't doing well, was hard.

"I used to get depressed about it," he tells me. "One weekend I'd be driving a Formula 1 Surtees in the Canadian Grand Prix, or the German GP or the British GP, and sort of qualifying 14th, 15th, 18th. And really feeling sick about it. But the next weekend, I'd go out against the same drivers and be on pole position in sportscars! With Andretti and those style of drivers. And I could outqualify them! So if I was doing that, I must have been okay," he says. It was the sportscar racing, then, that was the silver lining around the single-seater cloud. "I didn't get as depressed as if I hadn't done sports cars - I'd have probably shot myself. But I would say, never mind Derek, you blew them all away last weekend, in sportscars!"

While Bell might not have managed a "good year" in Formula 1, he still did something that so many drivers wish for, but so few actually do. He raced for Ferrari. And the chance came to him very early on in his career. "After three races in F2, I got a call from Ferrari ?Mr. Ferrari," he emphasises. "Would I go have a test drive?" For Bell, the question was almost rhetorical, because when Enzo Ferrari calls you and asks if you'll have a test drive, oh, you'll have a test drive! So off he went to Monza. The tale of how a Ferrari mechanic warned him that if he crashed the "red" car, he'd never drive another "red" car again, is part of motorsport lore now. Fortunately for Bell, he returned the Ferrari to the pits unscathed.

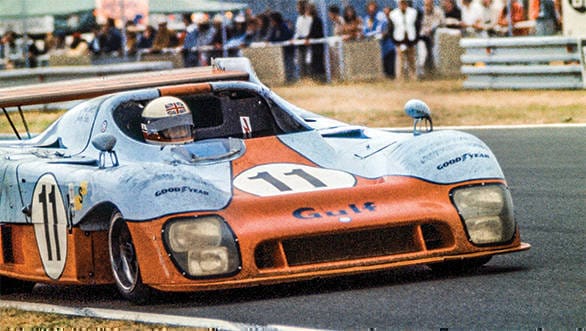

Derek Bell in the Le Mans-winning Mirage GR8, that he and Jacky Ickx piloted to victory in 1975

Derek Bell in the Le Mans-winning Mirage GR8, that he and Jacky Ickx piloted to victory in 1975

"I guess I did all right, because they had twelve drivers, and for some reason I got the drive. And I was then a Ferrari works driver in my fourth year. So it was pretty good," he says, and racing the factory Ferrari 166 certainly was a step up from racing the Brabham BT23C for his stepfather's Church Farm Racing Team. Along with the chance to drive for Mr. Ferrari, came the opportunity to interact with the great man. "I got to know Enzo quite well, which was an amazing experience. And even if I didn't have the greatest time of my life racing (with them), to race for Enzo Ferrari is pretty special. Even when I sit in a Ferrari now, like the one in that picture," he says pointing up at the screen where I see a Ferrari gliding over the tarmac on the Monaco GP circuit, "I think of Enzo. And, I was bloody lucky!" he says. There aren't too many racers out there who can boast as many firsts with Ferrari as Bell can - his first professional F2 drive, his first Formula 1 race, his first Le Mans. But there's just a hint of regret when he speaks of the Scuderia. "I never got on to being anything great at Ferrari, which is very sad. But I know I was good enough, because I knew how well I was doing around (in other series) all the time, but not when I was in the Ferrari!"

As I'm listening to Bell speak, I have to strain my ears rather a lot, because of the raucous roar of the engines on track. And I can tell that he's still itching to watch the racing, but he's far too polite to keep interrupting the interview, so he sits and continues to talk, only occasionally allowing himself to glance up at the screens. And as he speaks, not just because of his demeanour, but also because of what he's saying, one gets the feeling that this incredibly decorated racer is a man accustomed to consuming his daily humble pill. Which is why I wonder whether Bell is being deliberately self-effacing when he tells me that he sometimes wondered whether he was a "flash in the pan". Even though he was making rapid progress through motorsport, the question of whether or not he was good, or good enough, seemed to haunt him. "As I reflect on it now, I guess I must have been quite good. But at the time I had no confidence." After all, he wasn't the only driver who was moving on and making progress. "But nobody else went to Ferrari but me, and nobody else went to John Wyer (the man behind Gulf's success at Le Mans) but me," he says resignedly. It's amusing the way he seems to finally accept, in retrospect, that he really was good. But there's another reason Bell believes he really wasn't confident. "You know, I was naive. I guess these days people push you. And they go, 'Oh you're doing well.' You have a manager and a PR team and they give you all that publicity, and they say, 'You're great, you're great, you're great!' Whereas in reality I didn't have all that. I just had me and my family." And even though his stepfather, once convinced that Bell had a future in motorsport, tried to do everything in his power to make sure he could race, the rest of the family thought that he ought to get a regular day job and earn a living.

One can understand why his family felt the way they did though. It wasn't just about earning a living, and as Bell aptly puts it, none of the drivers of that era were in it for the money. But his most active years in motorsport were at a time when so many racing greats went out onto the track and never came back. He'd grown up idolising "Stirling Moss and Jimmy Clark," he tells me. The minute he says that, I realise I've never met someone who was familiar enough with the double world champion to refer to him as "Jimmy". And in his first season of Formula 2, Bell competed in the race in which Clark died. "I'd spent the evening with him and Graham Hill," he says of the weekend, "so it was very emotional." And then he comes up with a statement that is all too true about the era in which he raced - "The fact is a lot of the great people I met died."

Driving the No.11 Porsche 936 to his second Le Mans win in 1981

Driving the No.11 Porsche 936 to his second Le Mans win in 1981

Over the course of our conversation, the fact of just how dangerous motorsport was back in the day keeps coming up. At one point, while talking of happenstance, serendipity, and the fickle nature of lady luck, Bell speaks to me of how he was meant to drive for Brabham in Formula 1, which didn't happen. "I said to Gordon (Murray - the chief designer of Brabham) last night, 'You know if I had been in Formula 1 then, I'd have probably been dead now.'" It certainly was a cruel time in what so often is a very cruel sport. "When I look around and see Jackie Ickx, myself, Jackie Stewart, and Gerhard Berger who of course is much younger, but the people from our era - and we're here," Bell says. "But why are we here and half the guys aren't? The others are all dead. Why is that?" he says. The conversation's grown heavy as Bell reiterates a question that I think he's often asked himself. The answer, he tells me, is that he doesn't know. He has theories, "... I could put it down to being super lucky. And then I'd put it down to the fact that I was in sportscars. I don't know "

It's at this point that I begin to marvel at just how surreal an experience it is to have someone repeatedly tell me that he was just all right at motor racing, despite the fact that the statistics, the results sheets, the rivals, all might say something else entirely. I mean, think of Derek Bell and you're at once transported into a slightly sepia-toned era of motorsport, where race cars become a blur of blue and orange. There are images going through my mind, even as Bell speaks, of the Gulf Mirage GR8 that he shared with Jacky Ickx when they took their first win together at Le Mans in 1975. Or that Rothmans Porsche 936 and 956 and 962Cs that he drove to other Le Mans wins, along the way becoming one of the greatest Porsche drivers of all time. But it seems like thinking of the "what ifs" is just part of how Derek Bell analyses his motorsport past. He shrugs his shoulders and says of the past that didn't happen, "I might have stayed in F1 for a while, I might have been incredibly good. I doubt it. I think I'd have been quite good. I'd have been good, but I know I wasn't a Michael Schumacher." He pauses for a little longer this time, and I can almost see the thoughts whizzing around in his head, as he comes to a conclusion. "I know I wasn't as good as the best in my era. But I would have been a very good second place man," he declares.

Now, Bell isn't completely unaware of his strengths and weaknesses as a driver. He tells me that when he qualified on the third row of the grid at the 1968 Italian Grand Prix at Monza, his first ever Formula 1 race, a journalist he knew didn't rate him very highly as a driver, came up and said to him, "I didn't realise you were that good!" It mattered to him. "I thought I'd made it. Probably wrong!" he laughs. Later on though, he says he read of how his average lap times were faster than those of his contemporaries, and it occurred to him that he had the ability to be consistently fast. As soon as he says this, the self-effacing Bell appears to feel bad that he's said it at all. "I don't know. I never knew it at the time. Now I read certain journalist's books, and they write about it," he remarks.

1975 was a significant year in Bell's career, with the first victory at Le Mans being a sign of things to come. He has since gone down in history as one of the most successful sportscar racers of all time

1975 was a significant year in Bell's career, with the first victory at Le Mans being a sign of things to come. He has since gone down in history as one of the most successful sportscar racers of all time

Over a career that has spanned the better part of five decades, Bell has certainly learned a thing or two. The most important of which is, "Never underestimate yourself, but don't become super confident either," he adds. Being super confident leads to things like, "over driving the car, and then you hurt yourself." It almost seems as though Bell's entire career has been about walking this fine line. Of knowing he was good enough, never thinking he was too good, and racking up wins along the way. It's easy to understand why he's regularly rated as one of the nicest racers of the era by his contemporaries. And it's hard to imagine that his entire motorsport career is built on the fact that as a nine-year old, he'd hear the racecars going around Goodwood Circuit, just a few miles away from his home, and think to himself, "One day, one day "

Ever the gentleman, Bell was far too polite to tell me I'd far exceeded the time allotted for our interview

Ever the gentleman, Bell was far too polite to tell me I'd far exceeded the time allotted for our interview

In my experience, every single time I've spoken to Bell, the conversation seems to end right in the middle of a tale that has so much potential, but one that I don't get to hear the end of. This time is no different. I ask him a question on fear and the racecar driver, the answer to which I don't entirely get.

"Scared? Only once," he says to me. "I was scared at Spa. But it's such a long story, you could write a book about it!" he says before rushing off to other commitments.

Approximately six weeks after this conversation with Bell, I find myself wondering about the story that I didn't get to hear - about the time that the great Derek Bell was afraid. On a whim I decide to have a look at his social media feeds, and I open up Instagram on my phone. And I see a most amazing photograph. There's a biplane high up in the sky, and standing atop its wings, attempting a bizarre sport called wing walking, is 76-year old Derek Bell, pumping his fist in the air. I'm horrified, amazed, puzzled, perplexed, amused, and a few other things all at once. Whatever it was that happened at Spa-Francorchamps, must have been quite frightening if it managed to scare him. And the minute this thought crosses my mind, everything that's puzzled me about Bell suddenly makes sense. Like most things in life, it's got to do with perspective.

This story first appeared in the September 2018 issue of OVERDRIVE.